Animals and the simulation

Considers animals as programmed agents, conscious participants, or symbolic nodes in a possible simulation—via migration, magnetoreception, and collective behavior.

Are animals part of a coded reality? Simulation theory suggests that everything, from humans to animals, might operate within a programmed system. Animals, with their instinctive behaviors and unique sensory systems, offer clues about this potential simulation. Their precise migrations, predictive instincts, and group coordination mirror the logic of algorithms, raising questions about whether they are programmed entities, conscious participants, or symbolic patterns within a larger design.

Key ideas explored:

- Behavioral programs: Animals display precise, instinctive actions, like migratory paths or group movements, that resemble pre-set instructions.

- Conscious participants: Evidence shows some species may share in conscious experiences, challenging the notion of animals as mere automatons.

- Symbolic archetypes: Animals may represent deeper layers of reality, acting as messengers or nodes within an interconnected system.

Animals reveal the hidden structure of existence, whether through their magnetic navigation, collective intelligence, or spiritual resonance. They invite us to view reality not just as observers but as co-participants in a shared simulation.

If this resonates, your journey into the layers of reality has already begun.

Animal Consciousness in Varied Forms with Tom Campbell

Animals as Programs, Agents, and Symbols

Viewing animals through the lens of simulation theory gives us a fascinating framework to explore their roles as behavioral programs, conscious beings, and symbolic patterns. This perspective suggests that animal behavior - whether instinctive, intentional, or symbolic - mirrors the underlying "code" of our perceived reality.

Animals as Behavioral Programs

One of the earliest perspectives on animals saw them as automatons - essentially, living machines running pre-set scripts. René Descartes famously argued that animals operate purely through mechanical processes, devoid of consciousness. As he explained:

absolved people of any guilt for killing and eating animals

In this view, animals were complex systems reacting to stimuli, nothing more. Modern science, however, reveals just how intricate these "programs" can be. For instance, desert ants navigate home using dead reckoning, arctic terns migrate nearly 50,000 miles annually guided by the sun, honeybees communicate food locations through waggle dances, and rhesus macaques can distinguish quantities up to four with accuracy.

This phenomenon is sometimes described as "submentalizing" - a process where animals predict others' actions using observable cues, like gaze direction, rather than true mindreading. Psychologist C. Lloyd Morgan encapsulated this idea with Morgan's Canon:

In no case may we interpret an action as the outcome of the exercise of a higher psychical faculty, if it can be interpreted as the outcome of the exercise of one which stands lower in the psychological scale

From this perspective, animals function as finely tuned algorithms, each species programmed to maintain balance within its ecological niche. Yet, beyond these behavioral scripts, there’s evidence suggesting animals may also share in a conscious experience of reality.

Animals as Conscious Participants

Another perspective proposes that animals, like humans, actively experience the simulation. In April 2024, the New York Declaration on Animal Consciousness emphasized the "realistic possibility" of conscious experience in species ranging from reptiles to mollusks, cautioning:

If there's 'a realistic possibility' of 'conscious experience in an animal, it is irresponsible to ignore that possibility in decisions affecting that animal'

Scientific research supports this idea. In 2016, Christopher Krupenye and Fumihiro Kano used eye-tracking to study chimpanzees, bonobos, and orangutans as they watched videos of a human actor - dressed as King Kong - hiding in haystacks. The apes anticipated the human's actions based on his false belief about the actor’s location, rather than the actual one. Similarly, in 2007, Nicola Clayton and Nathan Emery discovered that California scrub-jays re-cached food when observed by another bird, suggesting they drew on their own past experiences to predict future intentions.

Crows, too, have demonstrated signs of subjective awareness, with their brain activity aligning more closely to what they perceive rather than external stimuli. Cephalopods, with over 100 million neurons, and honeybees, despite having just 1 million neurons, exhibit behaviors like higher-order learning and even "pessimistic" states after stressful events . If consciousness is indeed woven into the simulation’s fabric, animals might be co-participants, experiencing a shared yet diverse reality. Beyond their conscious interactions, animals also seem to embody symbolic patterns that hint at deeper layers of the simulation.

Animals as Symbolic Patterns

The third perspective sees animals as archetypes - symbolic figures embedded within the simulation’s narrative. Each species perceives a unique slice of reality . In simulation terms, these distinct perspectives function like sub-programs, revealing various layers of the system.

Take humpback whales, for example. In 1971, Roger Payne’s study in Science revealed that their songs follow a structured, repeating sequence (A, B, C, D, E), lasting between 7 and 30 minutes. These patterns were so precise that NASA included whale song recordings on the Golden Record sent aboard the Voyager probes in 1977, treating them as a coded message from Earth.

Philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein once remarked:

If a lion could speak, we could not understand him

This sentiment underscores the idea that animals experience reality in ways profoundly different from our own. Bees perceive ultraviolet patterns invisible to us, sharks detect faint electrical fields, and bats navigate through echolocation. In modern ecology, the concept of digital twins - virtual models of ecosystems like the Yangtze River - echoes ancient metaphysical hierarchies, positioning animals as agents within a tiered system of complexity. Anecdotal accounts, such as whales seemingly protecting humans or dolphins sensing pregnancies, further suggest animals may act as messengers in an interconnected reality.

Whether we see animals as programmed entities, conscious beings, or symbolic archetypes, each perspective offers a unique way to understand their role within a potential simulation. Perhaps animals embody all three facets, depending on the layer of reality we’re observing.

Coded Patterns in Animal Behavior

If reality operates as a simulation, the behaviors of animals might serve as windows into its underlying structure. From precise migrations to synchronized group movements, animals display behaviors that echo the logic of computational systems, suggesting the presence of pre-set instructions shaping their natural world.

Migration and Navigation Systems

Migratory animals navigate with precision that rivals GPS technology. In 2001, Kenneth J. Lohmann and his team conducted experiments on hatchling loggerhead sea turtles from Florida, exposing them to simulated magnetic fields. The turtles instinctively adjusted their orientation to align with magnetic fields mimicking those of Portugal and North Carolina, ensuring they stayed within the North Atlantic Subtropical Gyre. Researchers describe this ability as "inherited magnetic maps", an internal system that uses Earth's magnetic field as a natural coordinate grid.

The sensitivity of these systems is astonishing. Migratory reed warblers, for example, can detect magnetic inclination changes as small as 0.04–0.05 degrees, allowing them to pinpoint breeding sites with remarkable accuracy, while Manx shearwaters can sense even finer variations, down to 0.02 degrees or less. This process mirrors algorithmic pathfinding, where specific magnetic cues trigger precise directional adjustments. Lohmann explains that regional magnetic fields act as markers, guiding these adjustments.

Further evidence comes from studies on European robins in the 1960s by Wolfgang Wiltschko. When researchers altered magnetic fields using electromagnetic coils, the birds miscalculated their migration routes. This behavior is linked to cryptochrome proteins in their retinas, which may allow them to "see" magnetic fields through a quantum process known as the radical pair mechanism. Neurobiologist Steven M. Reppert from the University of Massachusetts Medical School highlighted the mystery of this ability:

Magnetism is the one sense that we know the least about

In another study, Bogong moths in Southeast Australia displayed a hard-coded orientation system. Specific visual neurons in these moths are tuned to fire maximally when oriented in a particular migratory direction - south in spring and north in autumn - regardless of the season. Even when Earth's magnetic field was nullified in flight simulator experiments, the moths maintained their seasonally appropriate trajectories. These behaviors suggest an innate programming that guides their movements.

Such precise navigation systems hint at deeply embedded processes, akin to computational algorithms, operating within animal intuition.

Animal Intuition and Prediction

Animals process environmental cues far beyond human perception, combining magnetic inclination and intensity into what some researchers describe as "nature's GPS". These internal systems function like feedback mechanisms, continuously correcting deviations between sensed input and their intended destinations.

Monarch butterflies provide a striking example. In 2013, when displaced 1,550 miles west of their usual migratory path, they continued flying along their pre-programmed southwest trajectory rather than compensating for the new location. This behavior underscores the existence of pre-loaded navigational instructions.

The geomagnetic field, present everywhere from mountain peaks to ocean depths, serves as a constant source of information. However, this signal can be disrupted. For instance, cattle that naturally align along the north–south magnetic axis lose this alignment near high-voltage power lines, which interfere with the Earth's subtle magnetic signals.

Beyond individual navigation, animals often display collective behaviors that reveal complex, coded interactions.

Swarm Intelligence and Group Behavior

Swarm intelligence provides some of the clearest examples of coded behavior in nature. Large groups of animals, such as flocks of birds or schools of fish, follow simple local rules to produce intricate, coordinated movements. This phenomenon resembles distributed computer algorithms, where decentralized actions combine to create emergent patterns. These biological behaviors have inspired computational models like the "Boids" algorithm for flocking and "Ant Colony Optimization" for solving pathfinding problems.

Honey bees, for instance, use a waggle dance to communicate the precise location of food sources relative to the sun, effectively encoding spatial coordinates through movement. African dung beetles navigate using the Milky Way or bright star clusters, marking the first observed case of an animal relying on galactic-scale cues for orientation. Similarly, desert ants use path integration - essentially dead reckoning - to continuously calculate their position by summing vectors of distance and direction, a process akin to algorithms used in robotic navigation.

In October 2025, ecologists employing "Crane Radar" successfully tracked a flock of about 60 birds along their migratory route, demonstrating the predictability and consistency of these patterns - hallmarks of systematic coding. The Manx shearwater, known to migrate approximately 6,200 miles, returns to the same nesting burrow year after year, suggesting precise storage and retrieval of navigational data.

Geophysicist Michael Winklhofer from Ludwig Maximilian University remarked:

Whenever one is dodgy, they use a more reliable one

This redundancy in navigational cues mirrors error-checking systems in computing, where backup processes activate when primary ones fail. Such mechanisms enhance survival by integrating multiple sensory inputs, reflecting an intricate layer of coordination that may point to the simulation's hidden framework.

Animals and Earth's Energy Systems

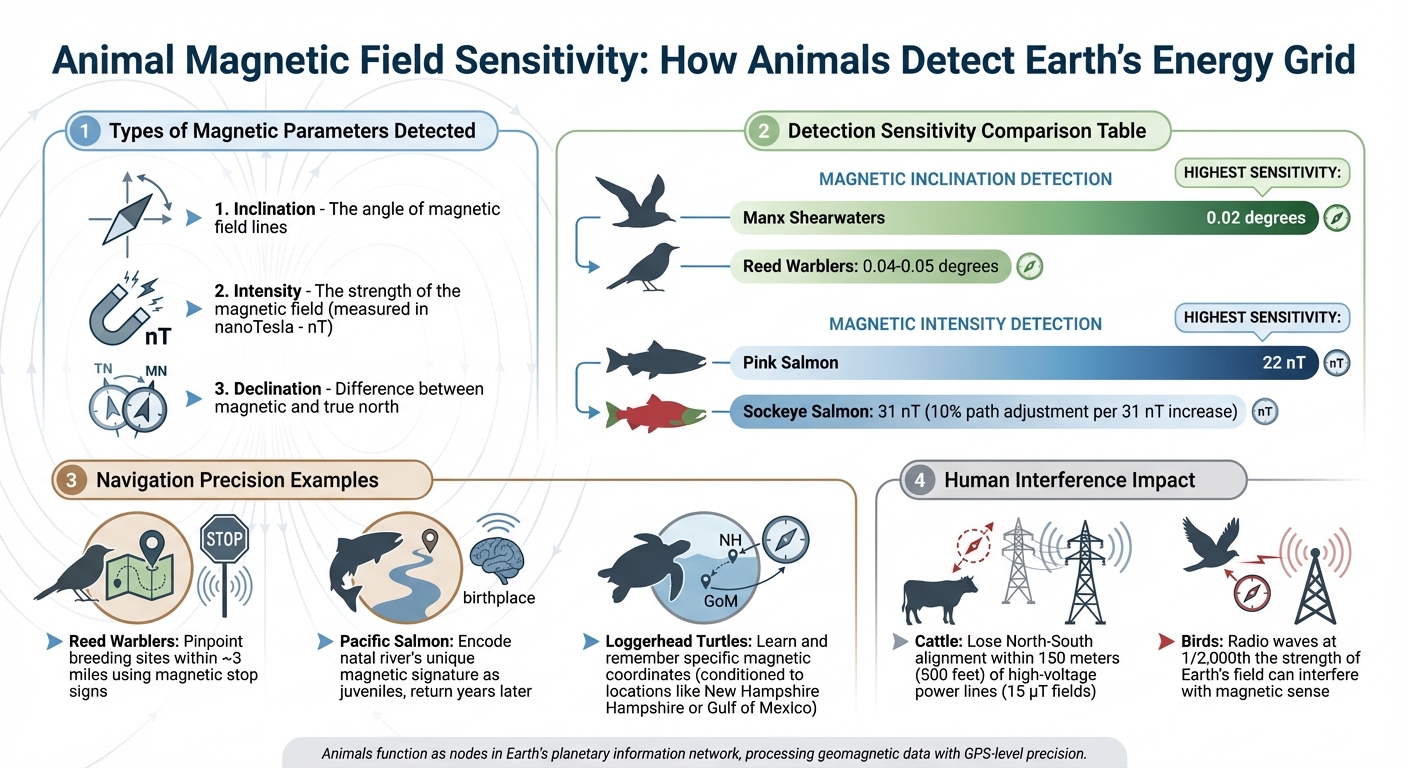

Animal Magnetic Field Sensitivity: Detection Thresholds Across Species

If we imagine reality as a simulation, animals might serve as gateways to Earth's underlying framework. Their sensitivity to geomagnetic fields, their roles within ecosystems, and their deep symbolic significance in human spirituality suggest they function as nodes within Earth's energetic web.

Sensitivity to Geomagnetic Fields

Animals don't merely navigate by Earth's magnetic field - they interpret it, almost like reading a coded map. This geomagnetic grid provides two critical types of information: direction (a compass for orientation) and position (a map for location). These cues vary across the planet based on three parameters: inclination (the angle of magnetic field lines), intensity (the strength of the field), and declination (the difference between magnetic and true north).

To interact with this magnetic grid, animals rely on mechanisms involving magnetite particles, light-sensitive cryptochrome reactions, and ion oscillations.

The accuracy of this navigation is extraordinary. For instance, sockeye salmon adjust their migratory paths by 10% for every 31 nT increase in magnetic field intensity, while pink salmon respond to changes as small as 22 nT. Shearwaters can detect inclination shifts of less than 0.02 degrees. Kenneth J. Lohmann, a biology professor at the University of North Carolina, captured the significance of this ability:

"The discovery of the magnetic map sense has revolutionized studies of animal navigation and transformed our understanding of how animals guide themselves, especially over long distances".

In 2014, Nathan Putman and his team demonstrated how Pacific salmon encode the unique magnetic signature of their natal river mouth as juveniles. Years later, they use this stored data to return to the exact same river for spawning. Similarly, research in May 2024 by Kayla M. Goforth's team at UNC-Chapel Hill revealed that juvenile loggerhead turtles could be conditioned to recognize specific magnetic signatures. When exposed to artificial magnetic fields replicating locations like New Hampshire or the Gulf of Mexico, the turtles learned to associate "rewarded" magnetic coordinates with feeding.

This ability goes beyond simple navigation - it's a form of data processing. Animals store, retrieve, and act on planetary information with a precision akin to GPS systems accessing satellite data.

However, human activity can disrupt this delicate connection. In 2008, Sabine Begall and colleagues analyzed satellite images of 8,510 cattle across 308 pastures worldwide. They found that cattle consistently aligned their bodies along the geomagnetic North–South axis. But within 150 meters (about 500 feet) of high-voltage power lines - producing magnetic fields as strong as 15 μT - this alignment disappeared. Similarly, radio waves at just 1/2,000th the strength of Earth's geomagnetic field can interfere with birds' magnetic sense. Such disruptions act like signal jamming, overriding the natural "broadcast" from the planet.

This intricate magnetic sensitivity suggests animals act as integral nodes within Earth's broader energy and information networks.

Animals as Nodes in Ecosystems

Ecosystems function as interconnected networks where animals play the role of processors, transmitting energy and information. Each species interfaces with the geomagnetic field at varying levels of precision, forming a distributed sensor network. For instance, migratory reed warblers use learned inclination values as "magnetic stop signs", marking the endpoint of their return journeys with an accuracy of about 3 miles.

This level of precision implies that animals aren't merely reacting to environmental cues - they're analyzing them. The collective behavior of animal groups, such as flocks, herds, or schools, demonstrates a "wisdom-of-the-crowd" effect. Together, these groups aggregate sensory data, producing patterns that resemble distributed computing systems.

| Parameter | Animal Sensitivity Example | Detection Level |

|---|---|---|

| Magnetic Inclination | Manx Shearwaters | 0.02 degrees |

| Magnetic Inclination | Reed Warblers | 0.04–0.05 degrees |

| Magnetic Intensity | Pink Salmon | 22 nT |

| Magnetic Intensity | Sockeye Salmon | 31 nT |

This distributed processing aligns with the idea of a simulated reality. In this context, animals act as nodes in a planetary information network, maintaining the flow of energy and biomass by interpreting geomagnetic data and triggering specific behaviors. As Lohmann remarked:

"The precision of a map is much less important than its utility to the organism. Natural selection will favor even a rough map if it enhances survival".

In a simulated framework, "natural selection" might simply reflect the refinement of algorithms, optimizing the system for stability and self-regulation.

Beyond navigation and ecosystem roles, animals hold a profound connection to human spirituality.

Animals as Spiritual Messengers

For centuries, animals have been seen as more than just creatures of the Earth. Across cultures, they are revered as messengers, guardians, and guides. Indigenous traditions often describe animal spirits as bridges between the physical and spiritual realms. Modern science now reveals that animals are finely tuned to Earth's deeper energetic layers, detecting frequencies and fields beyond human perception. They respond to subtle shifts in the planet's electromagnetic environment, offering insights into forces we are only beginning to understand.

Magnetism itself may serve as a bridge between the physical and the informational - the tangible and the coded. Whether through their precise biological "coding" or their symbolic resonance, animals seem to reveal the structured nature of reality. They aren't merely inhabitants of this simulation; they are active interfaces, offering glimpses into the architecture of existence and guiding us toward a deeper understanding of the world we inhabit.

What This Means for Human-Animal Relationships

If animals are seen as conscious agents or nodes within a simulated reality, our connection with them transforms. Rather than a hierarchy of dominance, it becomes a shared experience - a co-participation in an intricate network. This perspective invites us to reconsider how mutual influences have shaped the process of domestication.

Co-Evolution and Domestication

Domestication is not a one-sided affair; it’s a mutual exchange where both species evolve in response to each other's behaviors. Take dogs, for example. They didn’t simply become our companions by chance - they developed an extraordinary ability to interpret human facial expressions, head movements, and even subtle body language. This fine-tuned communication reflects a long history of adaptation.

The story of Clever Hans, a horse from the early 20th century, offers a fascinating glimpse into this dynamic. Hans seemed to solve math problems by tapping his hoof, but investigator Oskar Pfungst discovered that the horse was actually responding to tiny, subconscious head movements from questioners when they reached the correct answer. This phenomenon, now known as the Clever Hans effect, highlights how deeply animals tune into us. They don’t just observe - they process our gestures, gaze, and emotions as environmental cues, adjusting their responses in real time. In the context of a simulated reality, this interaction resembles two systems learning to communicate over centuries.

The Observer Effect and Animal Perception

The act of observing animals doesn’t just reveal their behavior - it actively shapes it. Research has shown that great apes, for instance, can predict human actions based on false beliefs about hidden objects. They model the human perspective to anticipate behavior. This isn’t mere reaction; it’s prediction, an ability to interpret what the human believes to be true.

This raises an intriguing question: How much of an animal’s behavior is shaped by our attention? In quantum mechanics, the observer effect suggests that observation collapses possibilities into a single outcome. With animals, our focus and perception may similarly influence their actions. A central debate in animal cognition is whether they are simply reading observable cues, like gaze direction, or if they are mind-reading - grasping internal mental states.

These findings challenge us to think differently about how we perceive and interact with animals.

Ethics and Respect for All Life Forms

Understanding animals as conscious participants in a shared simulation places a moral responsibility on us to treat them with respect. Modern neuroscience has dismantled the outdated notion that animals are mechanical beings incapable of suffering. Even creatures with relatively simple nervous systems, like bees, exhibit behaviors that suggest higher-order learning and perhaps some form of consciousness.

If animals are recognized as conscious beings, the staggering number of them killed annually for food or research becomes not only an ethical issue but also a failure to acknowledge the interconnected nature of life. Philosopher Kristin Andrews has pointed out:

animal welfare policies likely would need to expand as well

This ethical responsibility extends to all creatures. From octopi to cleaner wrasse to insects, evidence shows that many species experience frustration, pain, and even positive emotions. Practically speaking, this means creating environments suited to their unique needs and understanding that each species perceives reality differently. A bat navigating through echolocation, a knifefish sensing electric fields, or a spider detecting vibrations all experience the world through their own Umwelt - a term for the unique sensory world of an organism. Our role is not to impose our human perspective but to honor these varied ways of being.

When we view animals as co-participants in a shared simulation, every interaction becomes a chance to better understand the system - and our place within it.

Conclusion: What Animals Reveal About the Simulation

Animals, with their remarkable behaviors and abilities, offer a glimpse into the deeper architecture of our reality. Whether they act as behavioral programs carrying out pre-set patterns, conscious agents navigating their unique Umwelten, or symbolic archetypes that transmit meaning across existence, they remind us that reality is layered with complexity far beyond human understanding.

Consider the extraordinary examples: Arctic terns embarking on 50,000-mile migrations, nutcrackers recalling exact locations of hidden seeds, or humpback whales composing intricate songs. These actions are not random; they are embedded with intention and precision, hinting at a sophisticated blueprint guiding their behavior.

These observations challenge the human-centric view of perception. As James Bridle puts it:

The nonhuman world is filled with superhuman abilities: Consider the calculating powers of slime molds, the electrochemical sensibilities of fungi, the subterranean signaling of plants and trees, and the wayfinding abilities of birds and bees.

Animals reveal that human perception is but one window among countless others. A bat navigating through echolocation, a bird sensing magnetic fields, or a whale conversing across oceans - all experience reality through sensory dimensions we can barely imagine. Recognizing these diverse interfaces expands our appreciation for the interconnected system that sustains life.

FAQs

What does simulation theory say about animal consciousness?

Simulation theory opens up the idea that animals, much like humans, might exist within a crafted reality. Their instincts, behaviors, and interactions could operate as programmed features, carefully designed to sustain balance and intricacy within the system. On the other hand, animals might also be conscious entities with distinct roles, actively shaping the simulation’s flow.

Consider phenomena such as animal intuition, migratory patterns, or their deep connection to Earth’s energetic systems - these could hint at their intended purpose within this constructed framework. While this perspective remains speculative, it invites us to reconsider the depth of animal consciousness and its place in the grander design of existence.

What role do animals play in a simulated reality?

Animals can be viewed as symbolic markers or "program elements" within the layers of a simulated reality, reflecting deeper patterns and themes woven into the system. Their behaviors, instincts, and social structures often follow remarkably precise patterns - like migratory paths or specialized communication techniques - that might function as embedded "code" ensuring equilibrium or delivering subtle messages.

Take the honeybee's intricate waggle dance or the perfectly synchronized flight of bird flocks as examples. These actions not only serve ecological purposes but might also carry symbolic resonance. Animals often embody archetypes - wolves representing loyalty, butterflies symbolizing transformation - offering humans a lens to explore universal ideas within the simulation. Observing these natural patterns invites us to ponder the interplay between instinct, free will, and consciousness, and to consider the role animals play in shaping the broader architecture of reality.

How do animals' navigation skills suggest a programmed reality?

Many animals, including birds, sea turtles, and salmon, demonstrate an extraordinary ability to navigate with precision, often traveling vast distances to return to exact locations. This remarkable skill is tied to their innate ability to sense Earth's magnetic field, which functions as both a compass and a map. What’s even more astonishing is that these abilities are instinctual - young birds can embark on solo migrations without any prior experience, and sea turtle hatchlings instinctively find their way back to the beaches where they were born.

This phenomenon points to biological systems encoded within these creatures, enabling them to interpret environmental signals as if they were processing data from a built-in program. The consistency of these behaviors across such varied species suggests a deeper structure at play - almost as if the natural world operates on a set of informational rules, like a simulation where each organism follows its own pre-determined navigation patterns.