The Mandela Effect: Faulty Memory or Evidence of Glitch Correction?

A clear look at whether the Mandela Effect is caused by memory reconstruction and social bias—or hints at simulation glitches and shifting timelines.

The Mandela Effect is a phenomenon where large groups of people recall events, details, or facts differently from documented history. Named after the widespread false memory of Nelson Mandela dying in prison during the 1980s, it raises deep questions about memory and reality. While psychologists explain it through cognitive biases like reconstructive memory and social reinforcement, others suggest it could hint at anomalies like simulation glitches or parallel timelines.

Key examples include:

- Nelson Mandela's "death in prison": He was released in 1990 and passed away in 2013.

- Pop culture misrememberings: The Monopoly Man with a monocle (never existed), "Berenstein Bears" (correct spelling: Berenstain), and "Luke, I am your father" (actual line: "No, I am your father").

- Historical oddities: JFK's limousine had six passengers, not four.

Theories diverge between science, which attributes the effect to memory quirks and social influence, and metaphysical ideas like glitches in a simulated reality. Whether rooted in psychology or something more mysterious, the Mandela Effect invites us to reflect on how we perceive and trust our memories.

If this resonates, you’re not here by accident.

What Caused The Mandela Effect? (Complete Edition)

What Is the Mandela Effect?

The Mandela Effect describes situations where large groups of people misremember facts, events, or cultural details in ways that conflict with documented history. It’s not just an isolated memory slip by one person; instead, thousands can share the same mistaken recollection with absolute certainty.

What makes this phenomenon so striking is the emotional conviction tied to these false memories. People often hold onto them with unwavering confidence, even when presented with clear evidence to the contrary.

This challenges how we traditionally understand memory. Psychologists often attribute it to reconstructive memory, a process where the brain fills in gaps using pre-existing patterns, often shaped by social influences. Yet, for some, these shared errors spark deeper questions: Could they point to alternate realities or glitches in a simulated existence? Regardless of the interpretation, the Mandela Effect invites us to explore not just how our minds work, but also the nature of reality itself.

How the Term Began

The term "Mandela Effect" was first introduced in 2009 by paranormal researcher Fiona Broome. During a casual conversation, she shared a vivid memory of Nelson Mandela dying in prison during the 1980s. To her surprise, many others remembered the same event, even though Mandela was alive and went on to become South Africa's president.

Broome began documenting similar instances on her website, where people shared their own experiences of collective false memories. What started as a niche curiosity quickly gained traction online, as social media platforms amplified these stories. From brand logos to famous movie quotes, countless examples emerged where shared recollections conflicted with historical records.

This viral spread cemented the Mandela Effect as more than a psychological curiosity - it became a cultural touchpoint, sparking debates about its origins and significance.

Common Features of Mandela Effect Cases

What sets the Mandela Effect apart from ordinary memory slips are its consistent, defining traits. These characteristics blur the line between simple errors and something potentially more profound.

-

Collective Misremembering

Large groups of people consistently recall the same incorrect detail. For instance, a 2022 study in Psychological Science by Deepasri Prasad and Wilma Bainbridge at the University of Chicago tested participants on 40 well-known icons. For seven of these - including the Monopoly Man and Pikachu - participants correctly identified the image only 33% of the time. The majority confidently chose false versions, such as a monocle on the Monopoly Man or a black tip on Pikachu's tail. Even when asked to draw these icons from memory, many repeated the same inaccuracies. -

Strong Emotional Certainty

People experiencing the Mandela Effect often have an unshakable belief in their memory. Even when confronted with evidence disproving their recollection, they rarely waver in their conviction. -

No Clear Source of Confusion

Unlike typical memory errors, Mandela Effect cases often lack an obvious explanation. There’s no widely circulated fake image or misinformation campaign to explain why so many people share the same false memory.

These features continue to fuel debates: Are these just quirks of human memory, or could they hint at something more mysterious - a deeper layer of reality waiting to be uncovered?

Well-Known Mandela Effect Examples

The Mandela Effect reveals itself in various ways, spanning history, pop culture, and even geography. Here are some of the most striking examples.

Nelson Mandela's Death: The Origin Story

The phenomenon gets its name from a widespread false memory about Nelson Mandela. Many people distinctly recall him dying in a South African prison during the 1980s. However, Mandela was released in 1990 and lived until December 5, 2013, passing away at the age of 95.

One potential explanation for this collective misremembering is source confusion. Mandela's story may have been subconsciously mixed with that of Steve Biko, another anti-apartheid activist who tragically died in police custody in 1977.

"Memories reflect our interpretations of our experiences, and are not literal recordings of what happened."

– Daniel Schacter, Ph.D., Harvard professor and author

This example has sparked discussions about whether such shared errors in memory point to more than just psychological quirks, perhaps hinting at deeper anomalies in our perception of reality.

Pop Culture Misrememberings

Pop culture provides a wealth of examples where collective memory diverges from documented facts. A 2022 study by Deepasri Prasad and Wilma Bainbridge at the University of Chicago revealed that participants correctly identified the authentic versions of famous icons less than 33% of the time. Even when asked to draw these icons from memory, they often included incorrect details that matched others' false memories.

Some of the most notable cases include:

- The Monopoly Man: Many imagine him with a monocle, though he has never been depicted wearing one. This mix-up may arise from associations with stereotypical images of wealthy Victorian-era figures.

- Berenstain Bears: The beloved children's book series is often misremembered as "Berenstein Bears", despite its actual spelling being "Berenstain Bears."

- "Mirror, mirror on the wall": The famous line from Snow White is, in fact, "Magic mirror on the wall."

- "Luke, I am your father": In Star Wars, Darth Vader’s actual line is "No, I am your father."

- Shazaam: Many recall a 1990s movie called Shazaam, starring comedian Sinbad as a genie. However, no such film exists. This memory is likely a confusion with the 1996 movie Kazaam, which featured Shaquille O'Neal.

These examples highlight how false memories in pop culture are not just individual quirks but often shared across large groups, raising questions about the mechanisms behind such consistent errors.

Historical and Geographic Oddities

The Mandela Effect isn’t limited to pop culture - it also appears in historical and geographical contexts. For instance, some people vividly remember there being only four people in President John F. Kennedy’s limousine during his assassination. In reality, there were six passengers, including the driver and Secret Service agents.

Brand logos also seem to trigger false memories. For example, the Fruit of the Loom logo is often recalled as including a cornucopia, but it has always featured just fruit. Similarly, many Star Wars fans picture the droid C-3PO as entirely gold, even though one of his legs is silver below the knee.

| Subject | Common False Memory | Actual Fact |

|---|---|---|

| Nelson Mandela | Died in prison in the 1980s | Released in 1990; died in 2013 |

| JFK Assassination | 4 people in the limousine | 6 people in the limousine |

| C-3PO | Entirely gold body | Has one silver leg |

| Fruit of the Loom | Logo includes a cornucopia | Logo features only fruit |

These examples demonstrate how collective memory errors can span a wide range of topics, from historical events to everyday imagery. They invite further exploration into why such patterns of misremembering occur and whether they reflect deeper aspects of human cognition - or perhaps something even stranger.

The Memory Science Explanation

Before diving into theories about reality glitches, it helps to understand what neuroscience reveals about how memory operates. These insights shed light on why so many people share identical false memories.

How Memory Reconstruction Works

Each time you recall a memory, your brain doesn’t replay a perfect recording. Instead, it reconstructs the memory by pulling fragments from different parts of the brain.

"Memories do not preserve a literal representation of the world; memories are constructed from fragments of information that are distributed across different brain regions."

– Daniel L. Schacter, Professor of Psychology, Harvard University

This reconstruction relies on schemas - mental frameworks your brain uses to fill in gaps. When you can’t recall something fully, your mind fills in the blanks with what "makes sense" based on familiar patterns or stereotypes. These schemas often draw from cultural norms or common expectations.

Another quirk of memory is that the brain tends to store the gist of an event rather than every detail. In experiments using the Deese-Roediger-McDermott paradigm, researchers found that 50% to 80% of participants confidently "remembered" seeing a word that wasn’t on a list, simply because it fit the theme of the other words. This tendency can make memories lean toward more familiar or expected patterns.

Source misattribution is another major factor. This occurs when you remember information but forget its origin. Take, for example, Jim Carrey’s parody of Sally Field’s Oscar speech. Over time, many people remember his version as the original, blending the parody with the real event.

| Cognitive Process | How It Creates False Memories | Real-World Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Schema Filling | Brain fills gaps using cultural expectations | Imagining the Monopoly Man with a monocle because it "fits" the wealthy stereotype |

| Gist Processing | Focus on general themes rather than details | Misremembering "Berenstein" because "-stein" feels more familiar |

| Source Misattribution | Forgetting where a memory originated | Mixing up movie parodies with actual scenes |

| Social Reinforcement | Group agreement strengthens shared false memories | Online communities collectively affirming events that never happened |

These mental processes are only part of the puzzle. Our social environment amplifies these errors even further.

Social Influence on Memory

Memory isn’t shaped in isolation. Social dynamics play a big role in reinforcing false memories. When others describe a memory the same way you recall it, your confidence in its accuracy grows - even if the memory is incorrect.

A study conducted by MIT in March 2018 analyzed 126,000 stories shared on Twitter between 2006 and 2017, involving 4.5 million tweets from 3 million users. The researchers found that false information was 70% more likely to be retweeted than accurate facts. Across all types of content, hoaxes and rumors spread faster and reached more people.

This phenomenon ties into the illusory truth effect, where repeated exposure to false information makes it feel true over time. For example, when thousands of people online claim to remember Nelson Mandela dying in prison, that collective belief can overshadow your own uncertain memories.

"Do you think something sounds accurate because you read it a lot, or because you actually have multiple pieces of evidence for it? That's what I worry about: how basic repetition, familiarity and fluency can distort people's knowledge about the world."

– David Gallo, Professor of Psychology, University of Chicago

The Mandela Effect is a striking example of how reconstructive memory processes - like schema-filling, gist processing, and source misattribution - combine with social reinforcement to create shared false memories. Studies of real-world events show that 76% of participants made at least one error when recalling specific details. The Mandela Effect simply highlights cases where these errors align across large groups of people.

The Simulation Theory Explanation

Some theorists argue that the Mandela Effect isn’t simply a matter of faulty memory but could instead point to glitches in a programmed reality. These so-called glitches might not just alter our memories but could even reshape the structure of reality itself.

The Glitch Theory

This idea compares the Mandela Effect to a software bug. For example, when countless people vividly recall the Monopoly Man wearing a monocle - a detail that has never been part of his design - simulation theorists suggest this isn’t collective confusion. Instead, they view it as a "system update" that retroactively changed the object's history within the simulation's database.

"Others believe the Mandela effect demonstrates that we live in a simulated reality created by a higher intelligence. These memory errors, they say, are the equivalent of software glitches - like in the movie The Matrix."

– Massimo Polidoro, Investigator of the Paranormal and Author

Several mechanisms are proposed to explain these anomalies. One is timeline merging, where parallel realities briefly intersect, leaving some people with memories from an alternate version of events. Another involves external disruptions, such as high-energy experiments, which might trigger shifts into alternate dimensions. Lastly, there’s the idea of system corrections, where the intelligence overseeing the simulation updates reality, leaving traces of the "previous version" in the form of residual memories - akin to "cached" data from before the update.

What This Means for Reality

Under the glitch hypothesis, simulation theory challenges how we perceive existence. If reality can be edited retroactively, then your memories might not be mistaken at all - they could be accurate records of a prior version of reality. In this framework, the past isn’t fixed but instead remains changeable, subject to adjustments by the intelligence operating the simulation.

"The Mandela effect makes us doubt our own memories and even our sense of reality."

– Sarah Wells, Science Journalist

This perspective raises unsettling questions about personal autonomy. If the world around you can shift without your consent or awareness, how much control do you truly have? Are you an active participant in this reality, or merely an avatar navigating a system governed by rules beyond your influence?

Simulation theorists also suggest that objective reality might be a programmed construct, reacting to observation. Some even propose that the simulation uses on-demand rendering, where environments are only "loaded" when observed, to conserve computational resources. Memory glitches might occur when the system fails to fully render historical data with precision.

The cultural resonance of this theory is reflected in the 2019 film The Mandela Effect, which delves into these possibilities. Whether seen as speculative philosophy or a plausible scenario, the theory invites profound questions: How would you recognize if reality had been altered - especially when your own memories might be the only evidence of the change?

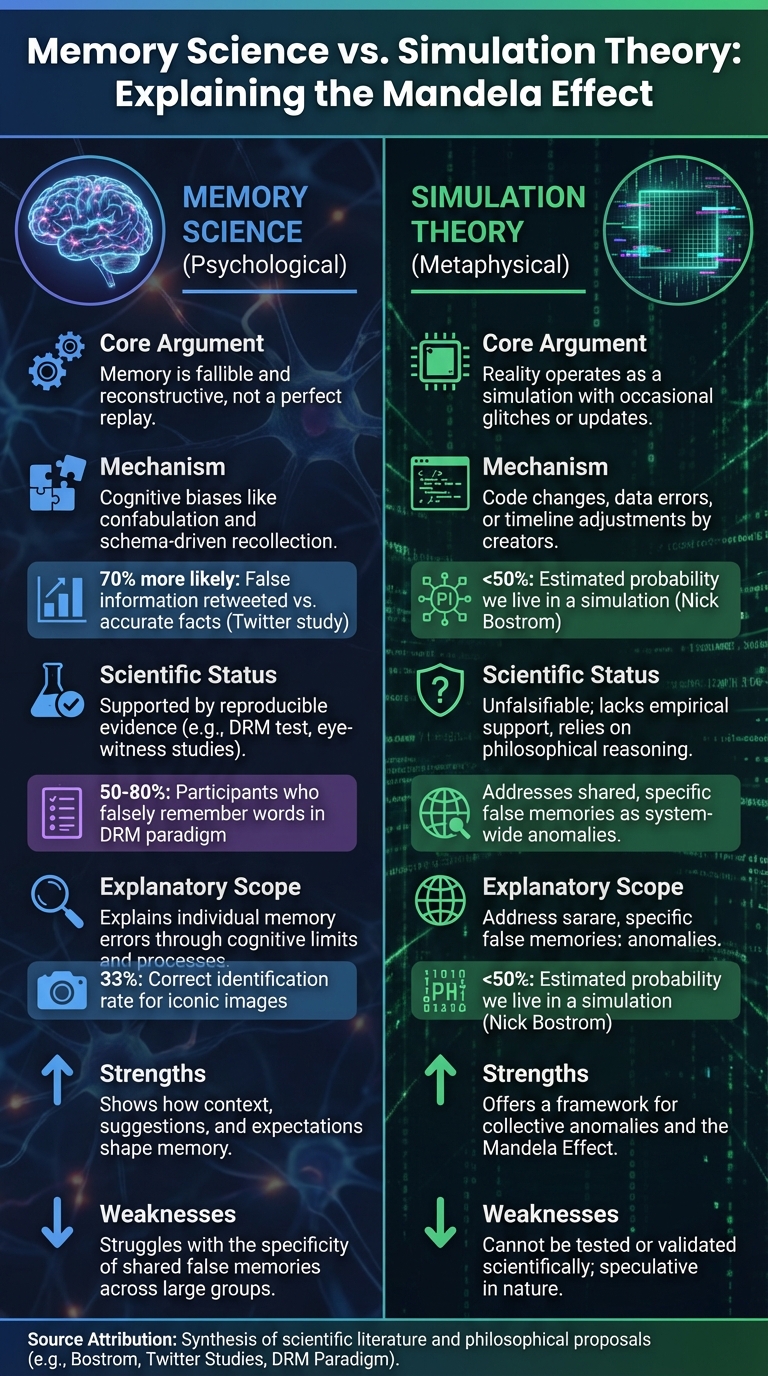

Memory Science vs. Simulation Theory

Memory Science vs Simulation Theory: Explaining the Mandela Effect

The ongoing discussion between memory science and simulation theory revolves around which perspective better accounts for the shared false memories experienced by large groups. This section compares the psychological and metaphysical viewpoints, exploring the strengths and limitations of each.

Psychologists have long established that memory is not a flawless recording device but a reconstructive process. Controlled experiments and social media analyses have shown how cognitive biases and social dynamics contribute to memory errors. For instance, a decade-long study of information spread on Twitter revealed that hoaxes and rumors are 70% more likely to be retweeted than factual information. This suggests that our brains rely on cognitive shortcuts to piece together memories, and social influence further amplifies these inaccuracies.

"Memory is a continuous process of creation and reconstruction, and memories change over time - even though we can be absolutely convinced of their accuracy."

– Massimo Polidoro, Investigator of the Paranormal

Despite these insights, memory science faces challenges in explaining why millions of unrelated individuals recall the same highly specific false details - such as the persistent belief that the Monopoly Man wears a monocle.

While psychology focuses on the brain's fallibility, simulation theory offers a bold alternative. This perspective suggests that shared false memories might be the result of changes or "glitches" in the simulated environment. According to this view, anomalies like the Monopoly Man's monocle could reflect edits or updates to the simulation's underlying code. However, since simulation theory cannot be tested or falsified, it remains more of a philosophical exploration than a scientific framework. Philosopher Nick Bostrom, who introduced the Simulation Argument, estimates the likelihood of our reality being a simulation at less than 50%.

Comparison Table

Below is a summary of how the two frameworks differ:

| Feature | Memory Science (Psychological) | Simulation Theory (Metaphysical) |

|---|---|---|

| Core Argument | Memory is fallible and reconstructive | Reality operates as a simulation with occasional glitches |

| Mechanism | Cognitive biases like confabulation and schema-driven recollection | Code changes, data errors, or timeline adjustments |

| Scientific Status | Supported by reproducible evidence (e.g., DRM test) | Unfalsifiable; lacks empirical support |

| Explanatory Scope | Explains individual memory errors through cognitive limits | Addresses shared, specific false memories |

| Strengths | Shows how context and expectations shape memory | Offers a framework for collective anomalies |

| Weaknesses | Struggles with the specificity of shared false memories | Cannot be tested or validated scientifically |

How to Investigate Mandela Effects Yourself

Whether you're drawn to theories of memory science or simulation, exploring Mandela Effects in your own life can be a fascinating journey. The aim is to distinguish between simple memory quirks and more puzzling anomalies, all while staying open to both psychological and metaphysical possibilities. The first step? Capture your memory as it exists before outside influences shape it.

Document and Verify Your Memories

Start by recording your memory without any external input. For instance, if you believe the Monopoly Man wears a monocle, sketch or describe exactly what you recall - every detail that stands out. Interestingly, studies reveal that nearly half of those familiar with the Monopoly logo mistakenly include a monocle when relying solely on memory.

Once you've documented your version, compare it with reliable sources such as official archives, original footage, or historical records. Keep in mind, even after seeing the correct version, your brain might still cling to false details. After verifying, check how your memory aligns with others' to see if your experience is personal or part of a shared phenomenon.

Compare Notes with Others

The collective nature of the Mandela Effect is what makes it unique - it revolves around "shared and consistent" false memories. By comparing your recollections with others', you can determine if what you're experiencing is a personal memory slip or part of a broader pattern. To avoid influencing others, ask them for specifics before sharing your version.

Look for identical details across multiple accounts. For example, if several people misremember the Monopoly Man with a monocle rather than a top hat or cane, it points to a shared Mandela Effect rather than random errors. Research into the Visual Mandela Effect shows that iconic images are often consistently misremembered, with participants selecting the correct version only about 33% of the time or less.

Identify Patterns and Biases

Consider whether your false memory aligns with common stereotypes or mental shortcuts. The brain uses "schemas" to fill in gaps, which is why so many people imagine the Monopoly Man with a monocle - it fits the archetype of a "wealthy Victorian gentleman". Ask yourself: Does this memory align with what I expect to see based on familiar cultural patterns?

Also, check if you're blending separate memories. For instance, the false recollection of a movie called Shazaam starring Sinbad likely comes from merging memories of the comedian Sinbad with the actual movie Kazaam featuring Shaquille O'Neal. Similarly, consider whether parodies, promotional materials, or misquotes have created an alternate version that feels just as real as the original.

Finally, be mindful of how repetition can reinforce false memories. Surveys show that about 60% of people recall the Monopoly Man with a monocle, but this widespread belief doesn't make it accurate. Instead, it highlights how familiarity can trick our minds into accepting something as true.

Conclusion

The Mandela Effect pushes us to reconsider how we perceive memory and reality. Cognitive science sheds light on this phenomenon by showing how our brains reconstruct memories, often filling in gaps with details that seem plausible. Research reveals that many people misremember events, even when those events are verifiable. This highlights just how prone human memory is to error.

Yet, the widespread nature of shared false memories raises questions that go beyond psychological explanations. As neuroscientist Caitlin Aamodt observes:

"The Mandela effect is still a fascinating case study in the quirks of human memory. For those who love thinking about how the mind works, it is perhaps even an example of the truth being stranger than fiction".

The persistence of metaphysical theories - despite their lack of scientific validation - reflects our curiosity about the unknown. These theories remain compelling because they touch on mysteries science has yet to fully address. This interplay between the explainable and the enigmatic encourages us to reflect on how our memories shape our understanding of the world.

Instead of seeking definitive answers, the Mandela Effect invites us to challenge our assumptions about both memory and reality. It reminds us that our recollections are not exact recordings but interpretations influenced by emotions, expectations, and social influences. Embracing this uncertainty can lead to a deeper curiosity about the nature of truth.

Ultimately, the Mandela Effect is less about proving one perspective right and more about the questions it raises. It prompts us to reflect on the reliability of our perceptions, the tension between personal and collective realities, and the boundaries of what we consider "truth." Whether you find yourself drawn to scientific explanations or intrigued by metaphysical possibilities, this phenomenon encourages an exploration of both the mechanics of the mind and the mysteries of existence - with a balance of skepticism and wonder.

FAQs

What are some well-known examples of the Mandela Effect in pop culture?

The Mandela Effect has intrigued many, with some unforgettable examples rooted in pop culture. Take the Star Wars saga, for instance - how often have you heard the line quoted as "Luke, I am your father"? Yet, the actual dialogue is "No, I am your father." Another curious case involves the Monopoly Man. Many distinctly recall him sporting a monocle, but he never has. Then there's Casablanca, a classic film often misquoted with "Play it again, Sam." In truth, the line is "Play it, Sam. Play 'As Time Goes By.'"

These instances reveal how shared misremembering can reshape our understanding of iconic moments, sparking deeper thoughts about the reliability of memory and the nature of reality.

What role do cognitive biases play in the Mandela Effect?

Cognitive biases play a pivotal role in shaping the Mandela Effect, influencing how we remember, interpret, and share information. For example, confirmation bias steers us toward recalling details that align with our existing beliefs or expectations. When others echo these same inaccuracies, it reinforces our confidence in these shared false memories. A classic case of this is the widespread misquote of Darth Vader's line as “Luke, I am your father,” when the actual line is “No, I am your father.”

Another contributing factor is misattribution, where we mistakenly link a memory to the wrong source. This can blur the lines between what we’ve genuinely experienced and what we’ve absorbed from external influences. Additionally, the availability heuristic amplifies the effect. When false information is frequently repeated - whether through social media or casual conversations - it becomes easier to recall, giving the illusion of universal truth.

Together, these cognitive biases weave a convincing tapestry of collective false memories. However, they arise from natural mental processes rather than any mysterious external force.

Does the Mandela Effect provide evidence of parallel universes?

The Mandela Effect has intrigued many, sparking debates about whether it hints at the existence of parallel universes or alternate realities. This phenomenon emerges when large groups of people recall events or details differently from how they are officially recorded. These collective "false memories" have led some to theorize that reality might occasionally shift or that dimensions could overlap.

Despite the allure of these ideas, most experts explain the Mandela Effect through psychological mechanisms such as cognitive biases, errors in memory reconstruction, and social influence. Our brains have a natural tendency to fill in gaps or reshape past events, which can lead to shared misconceptions. While the notion of parallel universes captivates the imagination, current scientific perspectives favor memory science over metaphysical interpretations.